Of the many books I read last year, these impacted me the

most. As usual, this is not a list of books written in 2018, but of the ones I

read last year. For some reason, I concentrated more on non-fiction, especially

memoir.

Fiction

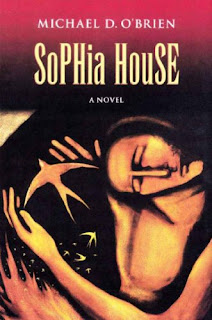

Michael O’Brien, Sophia House (2005): Set in

Warsaw during the Nazi occupation, a bookseller risks all to give refuge to a

Jewish boy who proves to be a precocious seeker after truth. Through their long

conversations in the dangerous setting, Pawel, the bookseller comes back to his

own faith. A moving story.

Jane Kirkpatrick, Emma of Aurora: A Clearing in the

Wild (2006), A Tendering in the Storm (2007), A Mending at the Edge (2008):

Trilogy based on the real history of a Christian colony from Michigan (on

the verge of becoming a sect) moving to Washington and finally to Aurora,

Oregon. The story of one woman’s growth into maturity and compassion. Promotes

the values and rights of women without being stridently feminist.

Ursula Hegi, Stones from the River (1994):

Story of Trudi, a dwarf, in Germany during the rise of Hitler. Small town life

of a marginal person, while larger issues surround the village, making many

people (a whole race) marginal. As an adolescent, Trudi was molested by some

boys her own age (including one who had been her friend), and in anger she

throws stones into the river. Later, she uses stones from the river to name

people and events in her life and to build an altar. Gradually as she matures,

she learns tolerance and forgiveness.

Nadia Hashimi, The Pearl that Broke its Shell (2014):

By an Afghani author about the sufferings of women under Islam. The stories

of two girls, separated by a century, one the great-great grandmother of the

other, interweave. Both suffered under the rule of the men in their lives, both

lived for a time disguised as boys, and both found ways of escape. Good

writing, important themes, cultural insights.

Non-Fiction

Clodaugh Finn, A Time To Risk All (2017): The

sub-title reads, “The incredible untold story of MARY ELMES, the Irish woman

who saved children from Nazi concentration camps.” This is a good academic

biography that focuses on Elmes’ time in Spain during the Spanish Civil War and

in southern France during World War II. It’s an incredible story, but doesn’t

go much into Elmes’ personal life, probably because she was such a private

person and no personal records remain. She worked for Quakers, but her own

commitment to Quakerism is unclear.

Tara Westover, Educated: A Memoir (2018): Amazing

memoir about what it means to be poor in the context of a right-wing cult in

America. About the role of education in breaking free and coming to live an

expanded and full life. Powerful.

Kathleen Norris, The Virgin of Bennington (2001):

One of my favorite books this year, this is Norris’ memoir of her college years

at Bennington (where she finally lost her virginity as well as her faith, but

discovered poetry), and her years in New York working at the Poetry Academy and

learning more about the life of a poet, struggling, and finally deciding to

leave New York for her grandmother’s ancestral home in North Dakota. Good

insights about poetry and poets and mentoring.

Jamie Wright, The Very Worst Missionary: A Memoir or

Whatever (2018): Wright’s typical rant against Christian missions,

based on her very limited experience as a missionary for two or three years in

Costa Rica. She seems to be trying to shock. She’s a skillful writer and an

intelligent person, but arrogance may be her downfall. She makes some good

points but needs to broaden her experience and read some history. Even so, I

enjoyed the book.

J. D. Vance, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and

Culture in Crisis (2016): Excellent and insightful on the

situation of the poor white working class in Kentucky, Ohio, etc. Vance

reflects on the factors that provided a way out for him, mostly people like his

grandparents who genuinely loved him and others who provided a positive

example. He talks about his ongoing battles to resist his learned responses to

conflict (shouting or escaping). The book illustrates the power of the

environment of poverty, but shows that it is not necessarily destiny.

Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees: What They

Feel, How They Communicate, Discoveries from a Secret World (2016): One

of my favorites this year, this is an excellent non-fiction study by a German

tree scientist about the complex underground connections (fungi) between trees

in an old growth forest. It deals with the differences between and old growth

and planted forests, the slowness of healthy growth, how trees handle

disasters—storms, fires, beasts, humans (the worse), how they feed each other,

how they share—or don’t share—light, how they migrate when necessary. Much more

complex than I ever dreamed.

Bob Woodward, Fear: Trump in the White House (2018):

A hard and terrible book to read, but an important one. Woodward carefully

documents details of Trump’s behavior, confirming the suspicions I’ve had of a

childish, stupid and very dangerous and controlling man. It’s important that

this is documented. God have mercy on us and on the whole world.

Douglas Preston, The Lost City of the Monkey God

(2017): Non-fiction, story of the discovery of two large pre-Columbian

cities in the Honduran rain forests. The difficulties of working in the snake

and bug infested atmosphere, the importance of the discoveries (still

happening), etc. The book shifted emphasis to the disease of Leishmania

braziliensis caused by sand flies, which the author and others on the

expedition contracted, with life-threatening and life-long consequences.

Discussion as to what caused the sudden demise of the cities, and the effects

of diseases, both from the Old and New worlds.

Lisa Ohlen Harris, The Fifth Season (2013):

The subtitle is, “A Daughter-in Law’s Memoir of Caregiving.” The events

happened in Texas but the author has since moved to Newberg where I live. An

excellent book and a compassionate story that doesn’t withhold or gloss over

the hard stuff. Well written.

Poetry

Jane Kenyon, Otherwise: New and Selected Poems (1996):

I love her poetry and find it accessible, much of it based on the ordinary

stuff of life.

James Wright, The Branch Will Not Break (2011)

: I love the title and the poem it’s based on, about waking up

after a hangover (and more). Others I love include “Trying to Pray,” “Beginning,”

and “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota.”

Scott Cairn, Endless Life: Poems of the Mystics (2014):

Cairns takes the writings of some of the church Fathers and Mothers (many

of them Orthodox, as he is) and turns passages into contemporary poems. Good

devotional material.